- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

On the seventh move of the most important decisive game, Black did what is now considered a critical error. When Black mixed up the moves in the defense of Caro-Cannes, White took advantage and organized an attack, sacrificing his horse. In just 11 of the following moves, White formed such a strong position that Black had no choice but to admit defeat. The loser declared about the unfair game of the opponent - and this accusation became one of the loudest in the history of chess tournaments. Twenty years later, he still has questions.

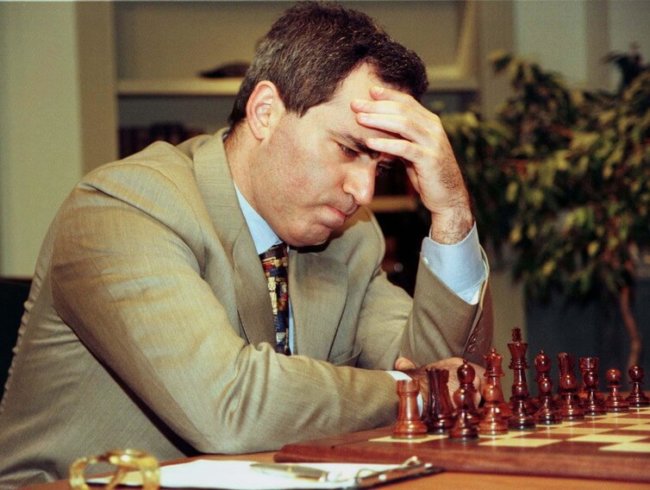

It was not an ordinary game of chess. Often, a defeated player can blame his opponent for an unfair game, but in this case, the then world chess champion Garry Kasparov was the loser. The winner was even more unusual: the IBM Deep Blue supercomputer.

The victory over Kasparov on May 11, 1997 made Deep Blue the first computer to beat the world champion in a match of six games with the standard time. Kasparov won the first game, lost the second and the next three tied. When Deep Blue won the final game, Kasparov refused to believe it.

Echoing the tricks of the chess machines of the 18th and 19th centuries, Kasparov said that the computer was controlled by a real grandmaster. He and his supporters believed that Deep Blue was too human to belong to the machine. Meanwhile, for many people convinced of computer performance, it became obvious that artificial intelligence reached a stage where it can surpass humanity - at least in a game that has long been considered too complicated for a machine.

The reality was that the victory of Deep Blue was ensured precisely by rigid, inhuman adherence to cold, rigid logic against Kasparov's emotional behavior. Not that the artificial (or real) intellect has demonstrated its own creative style of thinking and learning, no, it is the application of simple rules on a large scale that ensured the result.

That match was a signal to the social shift, which is gaining speed to this day. Deep processing of data, which relied on Deep Blue, is present today in almost all corners of our life - from financial systems that dominate the economy to online dating services that are trying to find us the ideal partner. What started as a student project helped to enter the era of large data (big data).

Human error

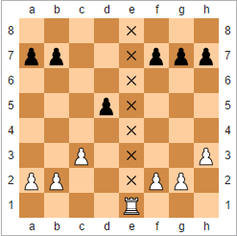

The basis of Kasparov's claims is presented to the move, which the computer made in the second match game, the first winning game for Deep Blue. Kasparov played in such a way as to force the opponent to take a fake pawn, a sacrificial figure, which allows to entrap the car into a trap. This tactic Kasparov used against human opponents in the past.

But the next move Deep Blue surprised Kasparov. Kasparov called him "humanoid." John Nunn, an English grandmaster, described him as "amazing" and "outstanding." This move broke the plan of Kasparov and turned his strategy. He was so worried that he could not return to the game and gave it away. Worse yet, he never recovered, played the next three games and made a fatal mistake, which led to the defeat in the last game.

That move was based on the strategic advantage that the player gains from creating an open line, a column of squares on the board (if viewed from above), on which there are no figures. It can create an attacking route, usually for rooks or queens, since there are no pawns blocking the path. During training with Grandmaster Joel Benjamin, the team of Deep Blue found out that an open line not only makes it possible to bring a rook to it. Tactics included drawing figures on the line and choosing the moment when you can open them.

When the programmers understood this, they rewrote the Deep Blue code to include these moves. During the game, the computer used a position with a possible open line to put pressure on Kasparov and force him to defend himself on every turn. This psychological advantage ultimately overwhelmed Kasparov.

When Kasparov lost, theories of conspiracies and speculation came into play. Conspiracy theorists claimed that IBM attracted a man during the match. IBM denies this, stating that in accordance with the rules, the only human intervention occurred between the games to correct errors discovered during the game. She also rejected the assertion that programming was adapted to the style of Kasparov's game. Instead, they relied on the computer's ability to find a huge number of possible moves.

IBM's refusal from Kasparov's request to hold a rematch and the subsequent dismantling of Deep Blue did nothing to quash suspicions. IBM also delayed the release of detailed computer records, which Kasparov also demanded, until Deep Blue was taken out of service. But the subsequent detailed analysis of the journal of the computer added new facts to the story and shed light on the serious errors of Deep Blue.

Since then, there are suggestions that Deep Blue won only because of an error in the code during the first game. One of the designers of Deep Blue said that when the glitch prevented the computer from choosing one of the moves that he analyzed, he instead made a random move, which Kasparov misinterpreted as a deeper strategy.

He managed to win the game, and by the second round the error was fixed. But the world champion seemed to be so shocked by the machine's excellent intelligence that he could not regain his composure and played too cautiously. He even missed a chance to get out of the open line tactics when Deep Blue made a "terrible mistake".

Whatever statement Kasparov on the topic of the match was not true, they indicate that his defeat was partially reduced to the weaknesses of human nature. He overestimated some of the moves of the car and became unnecessarily worried about her abilities, making mistakes that ultimately led to his defeat. Deep Blue did not even own methods of artificial intelligence, which today help computers to win in much more complex games, such as go.

But even if Kasparov was intimidated more than it should have been, there is no doubt about the tremendous achievements of the team that created Deep Blue. Her ability to beat the world's best chess player was based on the incredible processing power that led to the creation of the IBM supercomputer program, which paved the way for cutting-edge technology. What is even more surprising is the fact that the Deep Blue project was not an ambitious project of one of the largest computer manufacturers, but a student work of the 1980s.

Chess race

When Feng Xiong Xu arrived in the United States from Taiwan in 1982, he could not imagine what would become part of the intense rivalry between the two teams that had been trying to create the best chess computer in the world for almost a decade. Xu arrived at the Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania to study the design of integrated circuits, of which microchips are made, but he was also interested in computer chess for a long time. It drew the attention of the developers of Hitech, a computer that in 1988 was the first to beat the grandmaster, and asked to help with the development of hardware.

Soon, Hsiu quarreled with the Hitech team when he saw the architectural jamb in their design. Together with other graduate students, he began developing his own computer ChipTest, relying on the architecture of the chess machine Bell Laboratory. ChipTest's proprietary technology used "very large-scale integration" to combine thousands of transistors on a single chip and allow computers to find 500,000 chess moves every second.

Although the Hitech team started earlier, Xu and his colleagues soon caught up with her successor ChipTest. Deep Thought - named after the computer from Douglas Adams's book "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" - combined two specialized Xu processors and learned to analyze 720,000 moves per second. In 1989, he won the World Computer Chess Championship without losing a single game.

But in the same year Deep Thought lost to Garry Kasparov, the current world champion in chess. To beat the best grandmaster of the world, Xu and his team had to go much further. But now they had the support of the computer giant IBM.

Chess computers work by attaching a numerical value to the position of each figure on the board using the formula "valuation functions". These values can then be processed and sorted out in search of a better move. The first chess computers, such as Belle and Hitech, used several custom chips to perform evaluation functions and then combined the results.

The problem was that the connection between the chips was slow and consumed a lot of processing power. With ChipTest, Xu managed to redesign and repackage the processors into one chip. This eliminated a number of overhead processing costs and significantly increased the computational speed. While Deep Thought could handle 720,000 moves per second, Deep Blue used a large number of processors that ran the same calculations simultaneously to analyze 100,000,000 moves per second.

The increase in the number of moves that the computer could process was important, because chess computers traditionally used the methods of "full search" (brute force, brute force). Human players learn from past experience to instantly exclude certain actions. Chess machines at that time did not have this ability and instead had to rely on their ability to look ahead and see what could happen at every possible move. They used a full bust, analyzing the enormous number of moves, instead of focusing on a certain type of moves that would work for sure. The increase in the number of moves that the machine could see simultaneously allowed it to look much further into the future.

By February 1996, the IBM team again called Kasparov to battle, this time with Deep Blue. Although the car for the first time defeated the world champion in the usual time mode, Deep Blue lost the overall match with a score of 4: 2. His 100,000,000 moves per second was not enough to beat the man's ability to strategize.

To increase the number of moves, the team began upgrading the machine, exploring how to optimize a large number of processors running in parallel. Finally, a machine with 30 processors was formed, which, very importantly, controlled 480 custom integrated circuits designed specifically for playing chess. This custom design allowed the team to powerfully optimize parallel computing between the chips. The result was a new version of Deep Blue (Deeper Blue), capable of finding 200 million moves per second. For every possible strategy the machine could calculate up to 40 moves in advance.

Parallel Revolution

By the time when in May 1997 in New York held a rematch, the public interest was already at its peak. Reporters with cameras lined up and were rewarded with a picture of Kasparov blazing with righteous anger about his defeat at a press conference. The publicity of the match also made it possible to get a better idea of how far the computers went. Most people did not even know how Deep Blue would influence the further development of computers, and most importantly, how our society uses data.

Today, sophisticated computer models are used to support banking financial systems, develop better cars and aircraft, and test new drugs. Systems that study large data sets (often referred to as large data, or big data) look for meaningful patterns in planning public services, transport and healthcare and allow companies to target advertising to specific groups of people.

These are very complex tasks that require the rapid processing of large and complex sets of data. Deep Blue gave scientists and engineers a solid idea of the massive parallel multi-chip systems that made all this possible. In particular, they demonstrated the capabilities of a general-purpose computer system that controlled a large number of custom chips designed for a particular application.

The science of molecular dynamics, for example, includes the study of the physical motions of molecules and atoms. Custom chip designs allowed computers to simulate molecular dynamics and look ahead to see how new drugs could react in the body, like a miscalculation of chess moves in advance. Modeling molecular dynamics has helped accelerate the development of successful drugs, some of which are used to treat HIV.

For broad applications, such as modeling financial systems and data mining, designing specialized chips for a particular task in these areas would be prohibitively expensive. But the Deep Blue project helped develop methods for coding and controlling highly parallel systems that break the problem into a large number of processors.

Today, many data-processing systems use graphics processors instead of specialized chips. Originally they were designed to create images on the screen, but also processed information using parallel processors. Today they are often used on high-performance computers with large data sets and for launching powerful artificial intelligence tools. Here, too, the similarities to Deep Blue architecture are obvious: specialized chips (built for graphics), controlled by general-purpose processors, which increase the efficiency of complex calculations.

Meanwhile, the world of chess slot machines has developed significantly since the victory of Deep Blue. Despite his experience with Deep Blue, in 2003 Kasparov agreed to fight with two of the most famous chess machines - Deep Fritz and Deep Junior. Both times he managed to avoid defeat, although he still made mistakes that led to a draw. And yet both cars beat their opponents in 2004 and 2005.

Junior and Fritz marked a change in the approach to the development of systems for computer chess. While Deep Blue was a specially designed computer relying on the brute force of its processors analyzing millions of moves, the new chess machines were programs that use teaching methods to minimize the required searches. This allowed them to bypass the brute-force method with just the computing capabilities of a conventional personal computer.

Despite this breakthrough, we still do not have chess machines that would resemble human intellect in the game - and they do not need it. People make mistakes because they are emotional and are afraid for their reputation. Machines, on the other hand, mercilessly use logical calculations in the game. One day we may have computers that really think humanly, but the history of the last 20 years has led to the development of systems that are accurate to a high degree solely because they are machine-made.

The article is based on materials .

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment